How Vigorous is Your State’s Response to Violence?

Author and award-winning LA Times Reporter, Jill Leovey writes insightfully in her book, Ghettoside: Investigating A Homicide Epidemic, that: “Where the criminal justice system fails to respond vigorously to violent injury and death, homicide becomes endemic.”

As I read those words, I heard the author say that a jurisdiction that fails to respond vigorously to crimes of violence will suffer the consequences of sustained and higher levels of violence, injury, and death. Among the consequences that I envisioned, were the serious risks posed to the fulfillment of crucially important outcomes such as justice for the victims, resolution for their loved ones, and peace for their neighbors.

Justice is the very object of the pledge made every day in our schools, at our meetings, and certain events: “. . . with liberty and justice for all.”

While a murder victim’s survivors may never attain complete closure, they certainly seek and deserve resolution. Without it, their grief is compounded with feelings that for some reason justice has passed them by.

The effects of violent crime extend beyond the victims and their loved ones, to their friends and neighbors, and the community at large. Without peace, entire communities soon become victims themselves. People move, businesses close, jobs disappear, property values plummet and the City’s tax base erodes.

FBI Crime Data for 2019, reflects that firearms were used in 73.7 percent of the nation’s murders.

No, I’m not going to engage in a debate of whether there should be more guns or fewer guns or about what society should or should not be doing about them - our Constitution provides the framework for that. These matters are best left to lawmakers, their constituents, and the courts.

I am, however, going to focus my remarks on the need to respond vigorously to crimes committed with firearms.

From what I have observed during my fifty-plus years of experience in this area, I have found that when crimes involving firearms are not vigorously investigated, they are more likely to go unsolved. The more crimes that go unsolved, the more likely it is that victims will be denied justice, their loved one’s resolution, and their neighbors’ peace.

Vern Geberth points out in his book entitled: Practical Homicide Investigation, that understanding what has occurred can be determined only after a careful and intelligent examination of the crime scene and after the professional evaluation of the various bits and pieces of the evidence gathered by the investigators.

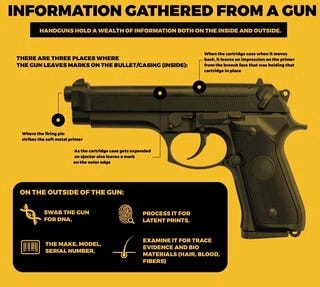

The bits and pieces of evidence can take many forms and be found in many places. When guns are involved there are certain bits and pieces of evidence that investigators must always look for many of which originate from inside and outside the gun itself.

From the inside of the gun comes data in the form of unique markings left on fired ammunition components by the internal working parts of the gun during the discharge process commonly referred to as “ballistics data”.

From the outside - comes identifying data in the form of make, model, and serial number that can be used to track the transactional history of the gun. In addition, other valuable forensic data, such as DNA, latent fingerprints, and trace evidence (e.g. blood, hairs, fibers, etc.), which can help police identify a person associated with the gun, can be found on the surface bearing areas of the firearm and ammunition components.

I refer to this as the inside-out approach in my book entitled: The 13 Critical Tasks: An Inside-out Approach to Solving More Gun Crime

In the book, I use the phrase . . . thoroughly and systematically investigate all crimes involving the use of firearms. I use it because much of the firearm-related violence we see today is repetitive in nature. One day a shooter may miss an intended target or cause property damage to send a warning. A day, a week, a month later - the shooter with the same gun may fire again and take a life.

Experience has shown over and over again that even the seemingly insignificant shootings, like those without injury or the common “Stop Sign” shooting, can often provide one of those key bits and pieces of evidence that can help connect a shooter to a much more serious crime. This same data from crime guns collected over the long term can also be of considerable strategic value in helping law enforcement identify patterns and trends in illegal gun markets.

Complicating matters is the fact that many criminals are highly mobile and evidence of their crimes becomes scattered across the city, state, and even national borders – today the crime-solving success of a murder investigation in City “A” may well hinge upon what a police officer in a small town 20 miles away does or does not do with the gun he or she takes into custody as part of a felony car stop or a found property complaint.

Therefore, I believe that in order to thoroughly and systematically investigate crimes involving firearms we must respond to the incident, canvas for witnesses, and search for and collect both forensic and other relevant data which may be available (e.g. gunfire location data, license plate data, security camera data, etc.). This information can be leveraged to generate, what is being commonly referred to in the business as crime gun intelligence (CGI).

I believe that we must collaborate within and across law enforcement organizations to find a sustainable way to collect and manage CGI - every crime – every time - across the affected region.

If you believe as I do – then we are in good company right alongside the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP).

In 2012, the IACP membership adopted a resolution number FC.028.a12 entitled: Regional Crime Gun Processing Protocols at its 119th Annual Conference in San Diego, CA. The resolution expressed the IACP’s belief that regionally applied crime gun and evidence processing protocols are a best practice for the investigation of firearm-related crimes and encouraged law enforcement officials, prosecuting attorneys, and forensic experts to collaborate on the design of mutually agreeable protocols best suited for their region.

The resolution calls upon agencies to address each of the following critical areas:

The thorough investigation of each gun crime & the safe and proper collection of all crime guns & related evidence.

The performance of appropriate NCIC transactions (e.g. stolen, recovered).

The timely and comprehensive tracing of all crime guns through ATF & eTrace.

The timely processing of crime gun test fires and ballistics evidence through NIBIN.

The timely lab submission and analysis of other forensic data from crime guns and related evidence (e.g. DNA, latent fingerprints, trace evidence).

The generation, dissemination and investigative follow-up of the intelligence derived from the protocols.

Timeliness, as noted in the bullets above, is critical to these processes as the longer an armed criminal remains unidentified and free - the greater the risk that more people will be harmed.

The IACP Resolution is almost ten years old now, so where are we today? Police departments and crime labs have adopted some or all of the elements of the resolution – in some shape or form. Though it’s hard to tell how many have and have not.

In some states, community voices called for a more vigorous response to crimes involving firearms as part of a state-wide public-policy approach.

Over the past ten years, lawmakers in five states – New Jersey, Delaware, Nevada, Indiana, and Illinois – have passed laws requiring that those crucial bits and pieces of crime gun intelligence - much like those identified in the 2012 IACP Resolution – be collected and timely managed.

This is an example of what such a public policy looks like in New Jersey:

NJ Rev Stat § 52:17B-9.18 - Findings, declarations relative to information relating to certain firearms.

“1. The Legislature finds and declares that to further provide for the public safety and the well-being of the citizens of this State, and to respond to growing dangers and threats of gun violence, it is altogether fitting and proper for the law enforcement departments and agencies of this State to fully participate, through the utilization of electronic technology, in inter-jurisdictional information and analysis sharing programs and systems to deter and solve gun crimes. To effectuate this objective, it shall be the policy of this State for its various law enforcement agencies to utilize fully the federal Criminal Justice Information System to transmit and receive information relating to the seizure and recovery of firearms by law enforcement, in particular, the National Crime Information Center System to determine whether a firearm has been reported stolen; the Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives E-Trace System to establish the identity of a firearm's first purchaser, where that firearm was purchased and when it was purchased; and the National Integrated Ballistics Identification Network to ascertain whether a particular firearm is related to any other criminal event or person.”

Time will tell how well these policies have affected positive change. After all, policies may drive but only adhered to policies sustain.

There are, however, many other states where big “P” policy isn’t driving the response to gun crime. This is not to say that police agencies are not implementing their own policies. Problems arise however when the response is vigorous in one place – but not the next.

Could it be that big “P” policymakers would rather spend their time, arguing over whether there should be “more guns or fewer guns” instead of how to better seek justice, resolution, and peace? You be the judge.

Or maybe - just maybe - it’s because most folks think that the thorough and systematic investigation of all gun-related crimes is already being done everywhere?

Well, it’s not – plain and simple - it’s not. There is a fix though.

Robert F. Kennedy once said that: “Every society gets the kind of criminal it deserves. What is equally true is that every community gets the kind of law enforcement it insists on.”