In the fight against crime and violence resolve must meet responsibility

Why I needed to revisit people, processes and technology.

Crisis-Driven Innovation with a balance of people, processes & technology [1]

In 2012, Stockton, California, became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy. The Stockton Police Department (SPD) was hit hard, losing nearly 100 sworn officers and over a quarter of its civilian staff. Even before the cuts, SPD was already understaffed by around 100 officers. As violent crime surged—rising to 71 homicides in 2012—Chief Eric Jones narrowed the department’s focus to two words: guns and gangs.

Despite the crisis, SPD found a way to innovate. A pivotal move was hiring a contract firearms examiner, who introduced a three-pronged approach to improve ballistic evidence processing:

Technology: New tools streamlined ballistic analysis and increased hit rates.

Processes: Operational changes boosted unit productivity.

People: The examiner assumed certification duties, eliminating the bottleneck of the overburdened state lab.

The changes overlapped neatly with my “three-legged stool” model—coordinated enhancements in people, processes, and technology, backed by leadership that prioritized reinvestment in ballistics technology. SPD’s focused strategy paid off. Homicides dropped to 32 in 2013—a 55% decrease.

Stockton’s turnaround shows that even when in deep crisis, targeted innovation, leadership, and an unshakable refusal to cede ground to Stockton’s criminal gangs can drive impactful reform.

The Three-legged Stool: People, Processes, and Technology

In his research paper, Testing the Effects of People, Processes, and Technology on Ballistic Evidence Processing Productivity, Ed Maguire put my three-legged stool metaphor to the test. He said: “Gagliardi hypothesizes that three elements are paramount: people, processes, and technology. He likens these three elements to the legs of a three-legged stool: Without all three elements in place, the stool will fall over (Gagliardi, 2019).” Maguire notes that “finding the right combination of people, processes, and technology, and applying it in a properly balanced manner” (p. 25) is essential for solving gun crime. Maguire concluded that: Gagliardi’s thesis is consistent with more general theories of complex organizations, which suggest that agencies are more likely to be effective when their environments, technologies, structures, and processes are properly aligned with one another (Maguire, 2003). [1]

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main . . . .” [2]

John Donne, 17th-century English Poet

The reality that I and many of you understand is that successful investigations of violent crimes committed with firearms require people aligned in well-coordinated teams involving local, state, and federal law enforcement; forensic experts; and prosecutors. All of them must manage certain handshakes and handoffs of data and information that are needed to identify, apprehend, and convict the perpetrator. [3]

Evolving the Framework: From Concept to Practice

Over time, I’ve found it necessary to expand the core concept of People, Processes, and Technology by adding greater clarity and action-oriented context. Today, in the world of crime gun intelligence, I believe these updated terms better capture what’s truly essential:

Cross-Jurisdictional Teamwork – People

Policy-Driven Tactics – Processes

Layers of Leveraging Technologies – Technology

These shifts reflect a more precise understanding of what drives meaningful outcomes in modern investigations.

Law enforcement has always operated on the foundational belief that there is no such thing as a perfect crime. According to Locard’s Exchange Principle, every contact leaves a trace. In theory, every crime is solvable.

Expanding on that principle, every agent who has ever served with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) will tell you: Every crime gun holds a story.

From the serial number etched on its surface to the ballistic markings inside and to the hands that held it, every firearm carries an abundance of potential evidence, waiting to be uncovered.

Solving firearm-related crimes begins with assembling the right cross-jurisdictional team—getting people to think and act together, across agencies and disciplines. When teams are aligned, potential evidence doesn’t fall through the cracks or get lost forever—it gets uncovered, connected, and put to work in the pursuit of justice, resolution, and peace.

The Three Slices of the “Investigative Pie” [5]

To better understand why cross-jurisdictional teamwork demands such focused attention, consider dividing the full investigative process into three distinct, sequential phases—or slices of the pie. Each phase requires coordination among multiple agencies and disciplines to ensure the case progresses without critical breakdowns or lost evidence.

The Three Phases of a Firearm-Related Investigation:

1. Respond & Collect

First responders secure the scene, gather evidence, and begin documenting the incident. Early decisions and collection methods can make or break the case.

2. Analyze & Extract Intelligence

Forensic experts and intelligence analysts process the evidence, linking ballistics, tracing firearms, and connecting the dots to identify suspects or crime patterns.

3. Identify, Arrest & Prosecute

Investigators, uniformed and tactical units, forensic personnel, and prosecutors work to build cases strong enough to lead to arrests, charges, and convictions in court.

There will be different people with different job descriptions and skills working within and across each of the three investigative phases. They will often report to different chains of command and different organizations as well.

For example, the response to a homicide may well involve personnel from Patrol, Crime Scene Investigation, Investigative Services, the Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office, and the District Attorney’s Office.

Similarly, the Extract & Analyze Phase will involve people with a different set of skills than the first responders, such as forensic experts, intelligence analysts who report to other chains of command, and organizations.

The same holds for the Identify, Arrest & Prosecute phase, especially in terms of how the Offices of the State and Federal Prosecutors coordinate actions with law enforcement officials and forensic labs.

It is important to know beforehand just how all of these investigative assets will think and act together as a team. “Handshakes”, in reality, formal agreements developed in collaboration with representatives from the key stakeholder groups can help make the process most efficient and effective. These agreements can help ensure the smooth, accurate, and timely “handoffs” of crucial information and evidence across the three phases. To ensure that all important information gets where it needs to go and when, any natural gaps that may exist between the phases (e.g., different chains of command, organizations, etc.) should be bridged with sustainable policies and procedures.

Therefore, a collaboration of all the affected stakeholders, representing law enforcers, prosecutors, and forensic experts, who possess expertise and experience in firearm crime investigation, can significantly increase the chances of successfully solving the crime.” [4]

Crimes such as murder and assault generally fall under the jurisdiction of a state and are managed within its criminal justice system. Within these systems, there are many interdependent stakeholder partners at the various state, county, and local government levels. They respond to and investigate crimes, collect and analyze evidence, develop and manage intelligence, adjudicate cases, and administer justice.

Certain crimes—those involving the use of firearms and drugs, for example—can also fall under the jurisdiction of the federal government and affect additional stakeholders who possess different assets, as well as special capabilities.

For example, in addition to its special agents, industry operations investigators, and professional support staff, the ATF has the National Tracing Center and eTrace for tracing the transaction history of confiscated crime guns and the National Integrated Ballistics Information Network (NIBIN) Program for linking crimes, guns, and suspects through computer-assisted analysis of fired evidence and test fires from crime guns and more.

Exposing the Gaps [5]

In complex, multi-agency investigations, handshakes and handoffs are vulnerable points where critical information can fall through the cracks, especially when coordination is lacking. Over 15 years of conducting 13 Critical Tasks Workshops globally have revealed recurring “gaps” in people, processes, and technology that often disrupt operations and delay justice, resolution, and peace.

For example:

Typical People Gaps:

Not enough personnel or funding.

Key partners are uncooperative or siloed.

Typical Process Gaps:

Outdated or rigid policies (e.g., old lab procedures causing months-long delays).

Backlogs and distance barriers prevent timely evidence submission.

Inconsistent use of tracing systems like eTrace.

Typical Technology Gaps:

Lack of access to critical tools like NIBIN in some states.

Underutilization of available technology.

Some gaps are more dangerous than visible obstacles—they’re “silent killers.” Agencies may falsely assume that tasks are completed and evidence is processed properly, when in fact, essential steps are missed entirely.

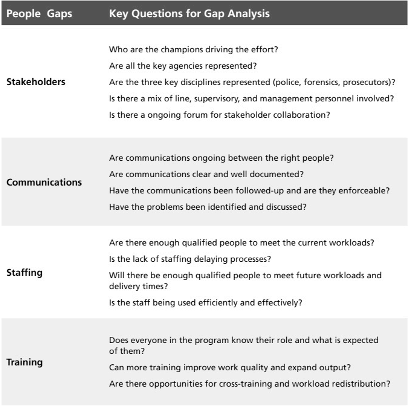

To combat this, a series of three Gap Analysis Charts—focused on people, processes, and technology—can help agencies identify and address these hidden vulnerabilities. [5]

Although not all-inclusive, the following three charts highlight some of the most common areas where gaps tend to occur across the domains of people, processes, and technology.

For example, in Gap Analysis Chart – People Gaps, common areas of concern include Stakeholders, Communication, Staffing, and Training.

Opposite each general area is a set of probing questions, designed to help identify potential causes of breakdowns and spark discussion about meaningful corrective actions.

GAP ANALYSIS CHART – PEOPLE GAPS

GAP ANALYSIS CHART – PROCESS GAPS

GAP ANALYSIS CHART – TECHNOLOGY GAPS

Balancing the Three-Legged Stool [5]

Using three standard flip charts labeled People, Processes, and Technology can serve as a simple but powerful tool for assessing and balancing your operations. This method helps ensure your approach is sustainable by focusing on three critical elements:

1. The work that must be done

2. The staff available to do it

3. The tools and technologies that enable staff to work efficiently and effectively

When all three legs are in balance, your system is stable. When one leg is weak or missing, the entire structure becomes vulnerable.

Flip Chart One — Processes

This chart is used to identify and map out new actions or protocols that stakeholders believe should be implemented under a presumptive approach, where certain investigative steps are assumed necessary and proactively carried out unless there’s a valid reason not to.

Example Process: Test-Firing All Seized Crime Guns for NIBIN Processing. This becomes the title of the flip chart. Beneath it, the team will list all the key sub-activities required to carry out this process effectively.

Sub-Activities Might Include:

1. Conduct a Safe Test-Fire

– Ensure proper safety procedures are followed

– Capture and preserve the fired cartridge case as evidence

2. Acquire the Exhibit in NIBIN

– Properly document and submit the cartridge case into the NIBIN system for analysis and lead generation

This approach ensures the entire process is broken down into manageable, actionable steps, with clarity on what needs to be done, by whom, and in what order.

Then move to Chart Two - People

Flip Chart Two — People

This chart is used to identify the personnel required to successfully carry out the process and sub-activities listed on the Processes chart. Stakeholders should focus on roles and skills, not just headcounts, ensuring the right people with the right expertise are aligned to each task.

Continuing the Example: Test-Firing All Seized Crime Guns for NIBIN Processing. To implement Sub-Activity #1 (conducting a safe test-fire and preserving the fired cartridge case) and Sub-Activity #2 (acquiring the exhibit in NIBIN), stakeholders estimate that the following personnel are needed:

a) 2 Firearm Examiners

– Trained to safely perform test-firing and document ballistic evidence

b) 3 NIBIN Lab Technicians

– Skilled in evidence intake, entry, and correlation within the NIBIN system

This chart helps expose potential staffing gaps, clarify roles, and estimate resource needs in order to operationalize the desired process efficiently and sustainably. Lack of funding for new positions is most often the main obstacle encountered for increases in staffing – they are expensive, as typically the organization incurs a funding commitment for the next 25-to-35 years and beyond into the employee’s retirement. The charts help ensure that the most expensive solution – new hiring – is put forward only after exhausting all other options.

Then move to Chart Three - Technology

Flip Chart Three — Technology

This chart identifies the tools, systems, and technologies that will be required to support the people executing the processes. It ensures that the right technology is in place to help staff perform their tasks efficiently and effectively.

This chart can also be used to:

Highlight existing technologies that are underutilized

Introduce new technology solutions that could speed up workflows, enhance productivity, or reduce staffing burdens

Support better balancing of the three-legged stool—ensuring people, processes, and technology are aligned and sustainable

Continuing the Example: Test-Firing All Seized Crime Guns for NIBIN Processing Technology needs might include:

NIBIN Acquisition Stations

– For digital imaging and entry of cartridge cases into the systemTest-Fire Ranges & Transportable Safe Bullet Capture Equipment

– Secure setups for safe and standardized test-firing inside and outside the labEvidence Management Software

– For tracking and linking evidence through the lab and investigative processRemote Access Tools or Cloud-Based Systems

– To allow off-site or multi-agency coordination and data sharing

By defining these requirements, stakeholders can better anticipate funding needs, implementation timelines, and training priorities to support the process end-to-end.

Working the Charts [5]

Three flip charts—People, Processes, and Technology—provide a flexible, easy-to-use visual aid that helps stakeholders explore what’s needed to implement a comprehensive crime gun intelligence-led approach to the firearm-related crime in their region.

Beyond the metaphor of a three-legged stool, a second way to visualize the role of the charts is to think of leveling a camera tripod. Depending on the terrain, you may shorten one leg, extend another, and leave the third as-is, adjusting and readjusting until the camera is properly aligned to capture the best possible image under real-world conditions.

A Real Workshop Example: Adjusting the Tripod in Action

During a live 13 Critical Tasks Workshop in 2008, a stakeholder group proposed a new process on their Processes Chart: "Test-fire all seized crime guns suitable for NIBIN processing."

On the People Chart, they estimated that this would require: “At least five additional specially trained lab personnel to perform test-firing and data entry.”

This estimate was met with a hard truth: hiring five new specialists was not financially realistic. Yet without that staffing, the new process would be unsustainable.

At that moment, the stakeholders noticed something important—the Technology Chart was still blank. This prompted a pivotal question: “Can technology reduce the need for additional personnel?”

That question led to a deeper inquiry. The assumption had been that all test-firing had to occur within the lab, which is why the staffing needs were so high. However, a discussion about technology innovations revealed a different path.

The group discovered that portable test-firing systems were now available—systems that were safer, smaller, and more affordable than traditional stationary water tanks used in labs.

They realized that test-firing could be:

Relocated outside the lab

Conducted by trained police officers at the firearms training range

Supervised under safety protocols already in place

This change dramatically altered the staffing requirements. The lab would no longer be responsible for the full test-firing process—only for NIBIN data entry of the collected evidence.

As a result, the estimated personnel need dropped from five to just one new lab technician—a much more realistic and sustainable solution.

Key Takeaway

The workshop participants were able to:

Redefine a process

Rethink personnel assumptions

Leverage technology to reduce the burden and improve the feasibility

By working across all three flip charts and adjusting the balance of people, processes, and technology—just like leveling a tripod—they identified a solution that was both effective and sustainable in providing substantial benefits for the government agencies involved and the public they serve. Moreover, and most importantly, the benefits produced would help to speed up investigations of firearm-related crimes, help stop armed criminals before they have the opportunity to re-offend and can do more harm, and to better seek justice for the victims of gun-related violent crimes, resolution for their loved ones, and peace for their neighbors.

###

[1] Edward R. Maguire et al., “Testing the Effects of People, Processes, and Technology on Ballistic Evidence Processing Productivity,” Police Quarterly 19, no. 2 (June 2016): 199–215.

[2] Donne, John. The Works of John Donne. vol III. Henry Alford, ed. London: John W. Parker, 1839. 574-5.

[3] Ray Guidetti, Geoff Noble, and Pete Gagliardi, “Challenging the Status Quo: How NJSP Developed Its Crime Gun Intelligence Program,” Police Chief (September 2016).

[4] Challenging the Status Quo: How NJSP Developed Its Crime Gun Intelligence Program, The Police Chief, vol. LXXXIII, no. 9, September 2016. Copyright held by the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Alexandria, VA.

[5] Gagliardi, Peter L. 2019. The 13 Critical Tasks: An Inside-Out Approach to Solving More Gun Crime. Second edition. Cote St-Luc, Quebec: Forensic Technology Inc., p. 204- 206.

3 steps in keeping the gap closed. Level the legs, keep adjusting to figure out what works best. If there are GAPS then stories like my grandmothers will just sit there. Finally, the gap was closed by leveling the legs. Then an outdoor partnership was made and here we all are. Working to keep the gap closed.

I’m currently partnering with a local organization that has GAP in their name and am definitely going to use your steps in a way that would benefit us and what we do. Just getting souls back on track. Filling the gap that they fell through. Good article Pete!