One of my favorite exercises during leadership training is deceptively simple, but incredibly revealing. I divide the class into three groups, what I call “syndicates.” I then challenge each one to brainstorm the traits essential for three types of leadership: general leadership, leadership specific to their profession (often law enforcement), and crisis leadership. After some spirited discussion, each group shares their list with the class, sparking lively debate and deeper reflection.

Unsurprisingly, many traits overlap. But one always makes the highlight reel: “decisive.” Whether it’s shouted proudly or sheepishly admitted after someone else says it, the moment that word hits the room, the response is almost universal: “Oh yeah, definitely.”

We want our leaders to be decisive. And when we’re in a leadership role ourselves, we want to be decisive. Yet, time and again, participants, ranging from first-line supervisors to seasoned executives, lament that decisiveness is in short supply. So, what gives?

Over 800 years ago, the brilliant medieval scholar Maimonides warned, “The risk of a wrong decision is preferable to the terror of indecision.” Fast forward to Theodore Roosevelt, who echoed this truth in plain American grit: “In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing.”

Still, many leaders hesitate. Why?

It turns out the roots of indecision run deep - spanning behavioral tendencies, risk aversion, overwhelming information, paralyzing uncertainty, organizational culture, poor communication, and that ever-present wild card: stress. Let’s not forget our biology either. Under pressure, the body’s stress response can hijack clear thinking, hijacking logic with adrenaline and cortisol.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s 2011 masterpiece Thinking, Fast and Slow illuminates this beautifully. He explains that our brains operate in two modes: System 1 and System 2.

System 1 is our brain’s autopilot: fast, intuitive, and energy efficient. It leans on experience, habit, and gut instinct. Think of binge-reading a thriller late at night, effortlessly absorbing every twist and turn, that’s System 1.

System 2, by contrast, is the brain’s heavy lifter. It’s slow, deliberate, and mentally exhausting. It demands focus and effort. If you’ve ever slogged through a dense technical manual, re-reading a paragraph five times to make sense of it, you’ve met System 2.

And here’s the kicker: Decisiveness hinges on knowing which system to use.

Most decisions, both personal and professional, can be handled with System 1. We draw on training, experience, and intuition to act quickly and effectively. But when we’re navigating unfamiliar terrain, overloaded with conflicting data, or lacking a mental roadmap, we must engage System 2. That means slowing down, thinking critically, and working harder to arrive at a sound decision.

That’s where structured decision-making models shine. They help leaders filter noise, organize thoughts, and move from chaos to clarity.

Let’s explore two powerful, time-tested frameworks:

Boyd’s OODA Loop: The Art of Adaptive Action

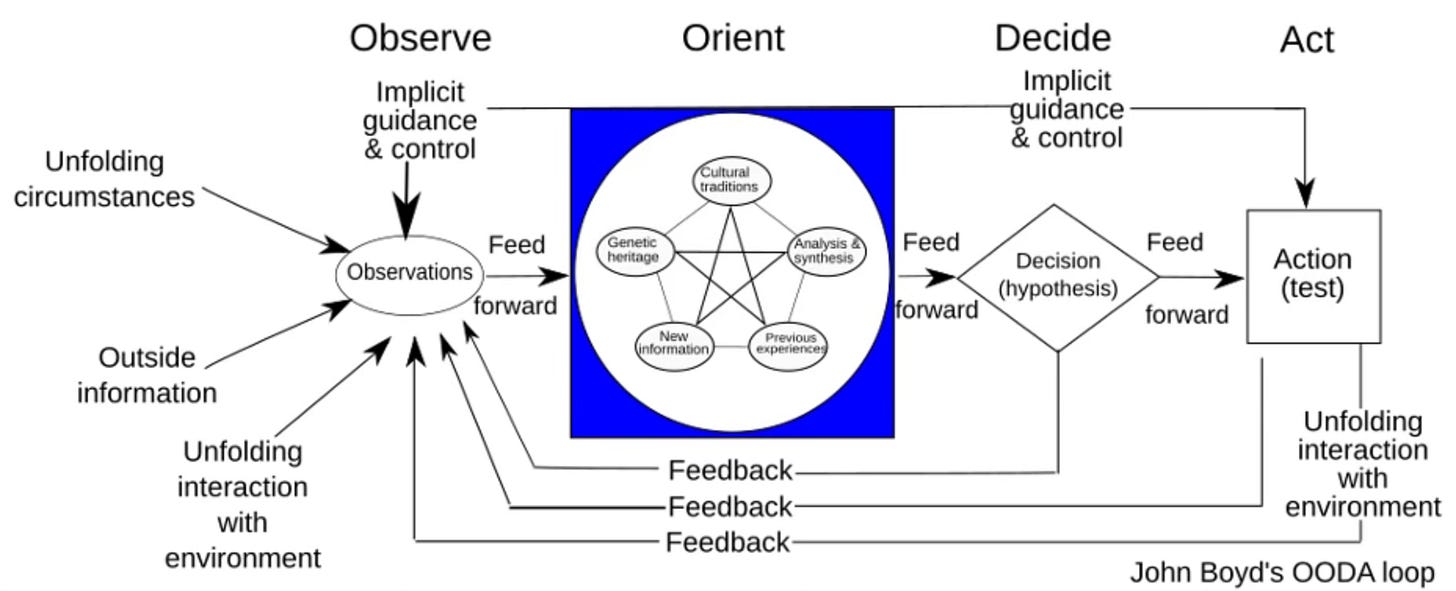

In the 1950s, legendary Air Force Colonel John Boyd developed the OODA Loop, a decision-making cycle rooted in agility and speed. Though born from air combat tactics, it has since shaped military strategy, business theory, and leadership at every level.

OODA stands for:

Observe – Perceive what’s happening. Gather data. Scan the environment. Spot patterns and disruptions.

Orient – Interpret what you see. Contextualize it using your experience, education, and training. Be mindful of biases and blind spots.

Decide – Weigh your options. Choose a course of action based on the available information.

Act – Execute. Then, observe the outcome and begin the loop again.

Think of it as a dynamic spiral, not a rigid cycle. The beauty of the OODA Loop lies in its feedback-driven nature. Each decision you make changes the landscape, which in turn informs your next move. The faster and more effectively you loop, the more control you exert over the situation.

SARA: A Problem-Solving Powerhouse

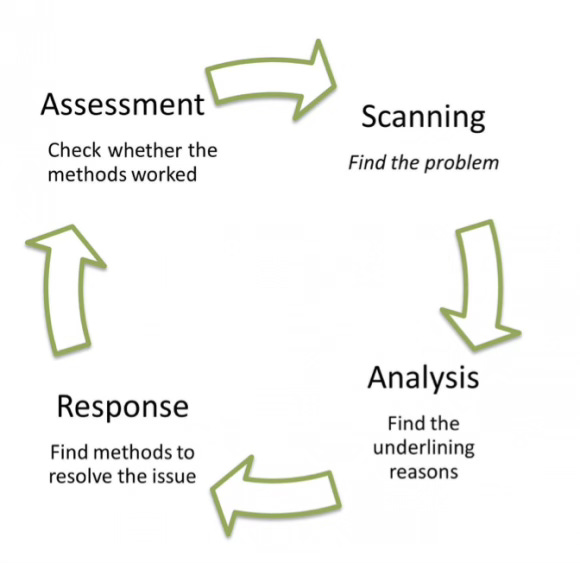

In the late ‘80s, criminologists John Eck and William Spelman introduced the SARA Model, a structured, problem-oriented framework that’s been a staple in law enforcement strategy ever since.

SARA stands for:

Scanning – Identify problems. Prioritize them. Gather data from internal and external sources.

Analysis – Dig deep. Separate symptoms from root causes. Anticipate ripple effects.

Response – Build a solution based on your analysis. Plan it. Implement it.

Assessment – Measure the impact. Did it work? What needs adjusting?

Like OODA, SARA is cyclical. If the problem persists or evolves, you re-enter the loop with new insights. It’s a methodical way to move from “We’ve got a problem” to “Here’s how we’re fixing it—and why.”

Whether you adopt OODA, SARA, or another decision-making model, consistency is key. Your entire team should speak the same language and use the same framework. If your organization doesn’t have a preferred model, experiment. Try one. If it doesn’t fit your culture or needs, try another. Adapt, refine, and keep iterating until you find a process that’s scalable, intuitive, and effective.

Leadership isn’t about never making a wrong decision - it’s about being courageous enough to make one at all. Inaction is the enemy of progress. So, next time you face the fork in the road, remember decisiveness isn’t just a trait - it’s a muscle.

And every time you flex it, you build stronger leadership.

What framework do you use when in System 2 thinking?

Sources:

Osinga, Franz P.B., Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, Routledge, New York, NY (2007)

The Evidence Based Policing App, “Refresher: SARA Model and Problem Oriented Policing”

Wikipedia, “OODA Loop”

George your work is beyond educational! Were you the inspiration for the role of the “Teacher” in the movie the DaVinci code?