What does John Miller, John Gotti, and Osama Bin Laden have to do with defining Crime Gun Intelligence?

I asked the question: Who were you more scared of - Bin Laden or John Gotti?

Without skipping a beat, he retorted, “Neither…Barbara Walters!”

That was my first real exposure to the legendary John Miller: author, investigative journalist, former Deputy Police Commissioner, and national counter-terrorism expert. He had been addressing a plenary session at the Naval Postgraduate School’s Center of Homeland Defense and Security.

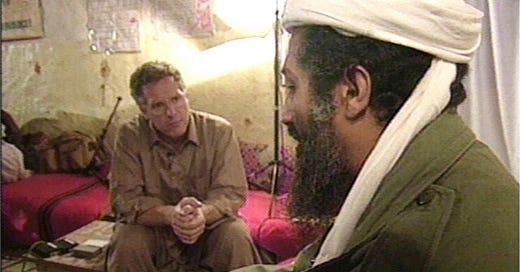

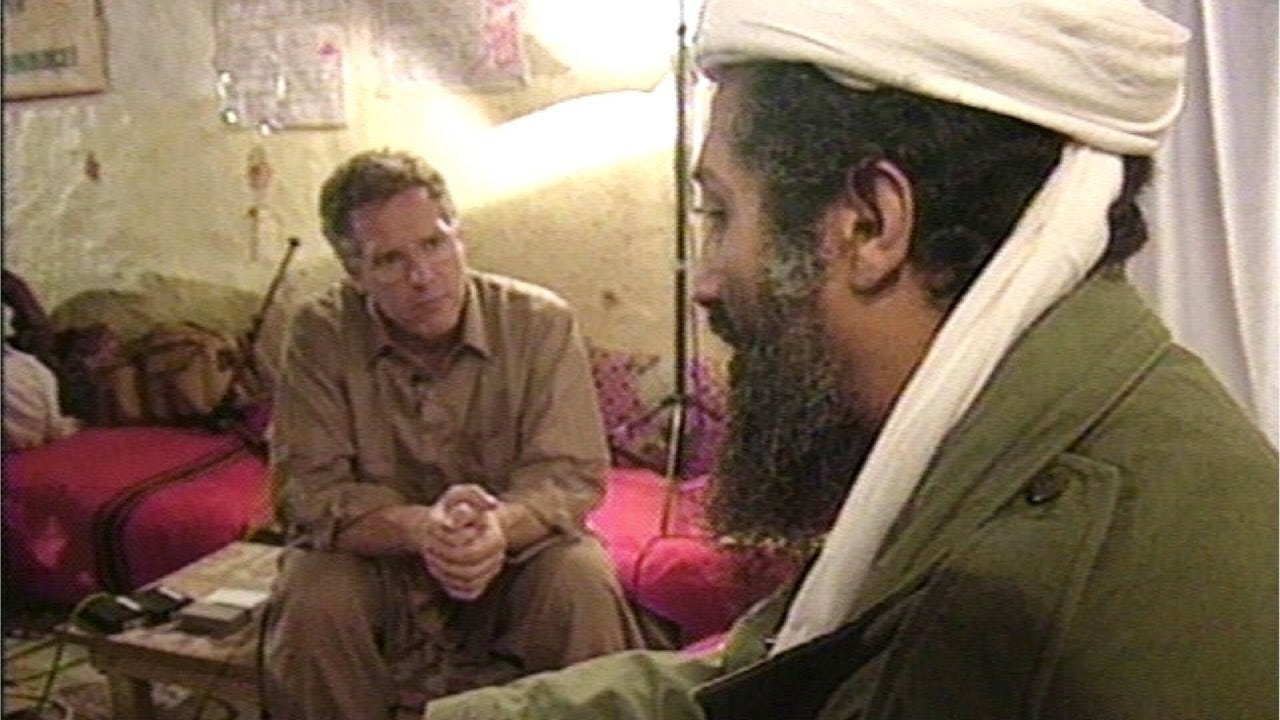

When John came to speak, he was working for the FBI. Being from the New York Metro Area and growing up with NBC News, I watched him shadow the head of the Gambino Crime Family in the streets of Gotham, and at the same time interview Osama bin Laden, the founder of the terrorist organization Al Qaeda in a tent in Afghanistan. So, I pitched my question to him.

What I got was a surprising and thought-provoking answer for sure, I should have expected as much from a man who asked questions of people for a living.

When you are in the presence of John Miller, you immediately recognize his ability to hold a conversation, whether one-to-one or one-to-many. Moreover, you quickly recognize his capacity to think fast and distill the complex down to the basic.

In that same brief in Monterey, John was able to define intelligence in a manner that not only had I never heard before, but to this day - 18 years later - still resonates with me. He said, “Intelligence is being able to understand problems, and really good intelligence is being able to do something about those problems we understand.”

We may be able to leverage his views of intelligence to now define the term “crime gun intelligence”.

Police intelligence

I cut my teeth as a young detective working the mob. It wasn’t long after John Gotti was convicted of killing Paul Castellano and traditional organized crime was in a state of flux. Funny that it was the same time that The Sopranos aired on TV. Back then police intelligence was more about informants and surveillance than “finished information.” We all had a stable of informants and conducted surveillance operations, both of which generated countless intelligence reports that would assist us in understanding the criminal conspiracies we targeted and developing investigations.

Yet, in the wake of Bin Laden's attacks on the United States, the world was not the only thing that was turned upside down. The police application of intelligence was shaken up a bit as well.

Police intelligence shifted its focus from collection to analysis. The intelligence cycle – the underpinning of our National Security intelligence model - became part of the domestic policing practice as the nation quickly had to sift through data to identify patterns and anomalies that could point to terrorists. We had to “connect the dots.”

It made sense then for intelligence-led policing (ILP)- a policing model from the United Kingdom that centered on the assessment and management of risk - to enter the lexicon of American policing. For me, Jerry Ratcliffe’s “3i Model” of ILP captured my attention on this important concept. Yet, the many definitions of ILP would seem unrecognizable to those grizzled detectives or special agents who focused their investigative prowess on La Cosa Nostra for so many years.

As fusion centers began to spring up in the mid to late 2000’s a new type of intelligence was suddenly thrust into the mainstream: homeland security intelligence. Now, cops and analysts could focus on more than just criminals with efforts encompassing terrorism, special events, catastrophes, border issues, cyber threats, and pandemics. Yet, similar to intelligence-led policing there are various definitions for this type of domestic intelligence.

As the focus distinctions of police intelligence continue to surface, I am reminded of John Miller’s prompt “Intelligence is about understanding problems, and really good intelligence is about doing something about those problems we understand.”

There’s a New Term in Town: Crime Gun Intelligence

When the ATF expanded its National Integrated Ballistics Information Network (NIBIN) and its eTrace initiative circa 2016 law enforcement began to focus more intently on gun crime and its cross-jurisdictional connections. It would be no surprise then that this movement would quickly be followed by a new police intelligence paradigm.

Crime gun intelligence (CGI) soon made its way into the vocabulary aimed at gun crime and “doing something” about violence in communities. Yet, as Ron Nichols pointed out in Crime Gun Strategy: A Playbook for Success, there are several definitions of CGI, and not all agree as to what the phrase means.

In a 2018 article for Police Chief Magazine entitled “In the Crosshairs-Crime Gun Intelligence, our ownPete Gagliardi suggested that one way to consider CGI would be to dissect it into its two basic elements. The first element being the term “crime gun”. Pete pointed out that the term crime gun had a specific definition coined by the Bureau of ATF back in the mid-90’s. This definition was shortened a bit by ATF in an endnote to the Introduction Section of its 2023 National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment, Volume Two, to read: A “crime gun” is any firearm used in a crime or identified by law enforcement as suspected of having been used in a crime.

In his article, Gagliardi suggested that the second element of a CGI definition - the intelligence part - could perhaps be gleaned from reports of the discussions that took place within the International Association of Chiefs of Police during their summits of 1998 and 2002. In his article, Pete did not attempt to draft a definition of CGI and one would be hard-pressed to find one today.

The Scout Mantra: Be Prepared

While we (at the RF Factor) aim to aid aspiring leaders in preparing for their future, we spend a significant amount of time exchanging ideas and writing about combating gun-related violence. When asked what CGI is it is paramount that we have an informative response at the ready.

We recognize that CGI can be many things. It’s more than just the intelligence that can be gleaned from crime guns, it's everything that can be gleaned about gun crimes as well.

Just like when the buck stops everywhere it stops nowhere - when we use a word like everything we really describe nothing.

Could there be a way of defining it in such a way as to be a bit more specific yet broad enough to allow for the flexibility to encompass the “many things”? As such, Pete and I thought we could take a crack at defining CGI that would help level-set our writings and discussions about CGI as well as focus on what Miller’s description of intelligence should offer: successful outcomes.

So, Pete and I rounded up two more experts in the field to trade ideas that would in time help us construct a clear definition of CGI. Frank Fernandez and Joe Brennan, two widely recognized individuals in this space, offered their insight into the task at hand.

In this pursuit of this definition, we acknowledged that what we would ultimately arrive at would be a mirror reflecting our collective insight at a given time. Hence, we also recognized that our comprehensive definition would be ever evolving where the words we chose would focus the reader's attention on not only the outputs involved in advancing CGI but also the intended outcomes Miller expressed related to “really good intelligence.”

The exercise proved to be fruitful when we arrived at the following:

Crime Gun Intelligence is information collected from crime-related firearms, shooting incidents, and other law enforcement sources, which when collated and assessed together is developed into timely investigative leads that can help police disarm criminals, prevent, and solve violent crimes, and positively impact our communities.

We can all agree that definitions serve as the bedrock of communication embodying the very essence of clarity in expression. Definitions breathe life into the police lexicon, infusing meaning into otherwise confusing concepts. While the importance of defining subjects like CGI resonates profoundly, we also recognized that there would be a risk of getting it wrong.

So in true John Miller fashion we had to ask ourselves the poignant question that would embolden us to take the leap and offer you a definition of CGI.

What are we more scared of: getting it wrong or being criticized?

Answer: Getting it right and being ignored.